As artificial intelligence applications have proliferated, their emerging use in court filings has become a topic of concern for some judges who have raised questions about accuracy and reliability.

The technology offers attorneys an automated means of handling a wide variety of routine tasks ranging from organizing electronic discovery materials to drafting legal briefs and conducting legal research.

But the rise of so-called virtual assistant applications, such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Google Gemini, has raised concerns in the legal realm from both an ethical and practical perspective.

In a recent court order, U.S. District Judge Karoline Mehalchick — presiding over the trial of seven people recently charged with weaponizing fentanyl to rob unsuspecting victims, including four who fatally overdosed — required participants in any of her cases to disclose any specific AI tools used in document preparation and to identify which segments of the documents were prepared by the program.

Anyone using artificial intelligence is also required to attest that a human checked the accuracy of the AI-prepared documents, under penalty of court sanctions.

“Increased use of Artificial Intelligence, particularly Generative AI (including, but not limited to, OpenAI’s ChatGPT or Google’s Bard), in the practice of law raises a number of practical concerns for the Court, including the risk that the generative AI tool might generate legally or factually incorrect information, or that it might create unsupported or nonexistent legal citations,” Mehalchick wrote.

Sporadic use

So far in Northeast Pennsylvania, the use of AI in court documents and for legal preparation appears to be sporadic.

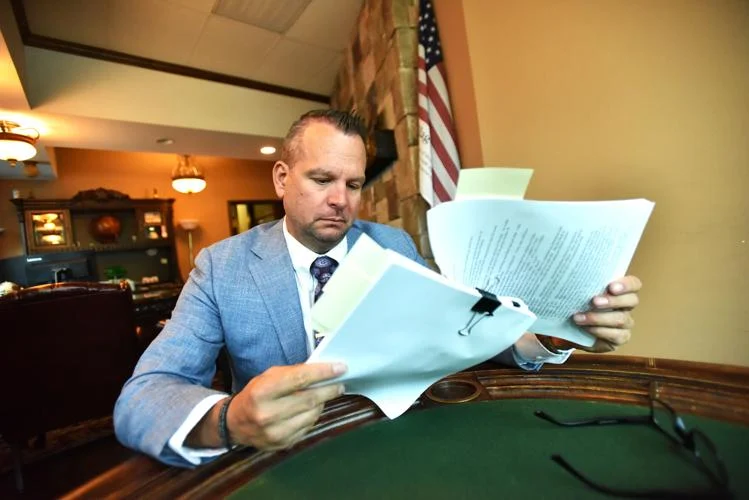

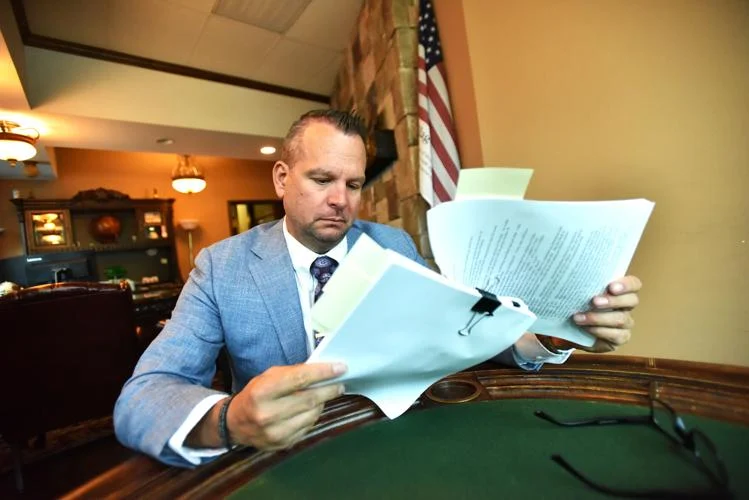

Attorney Michael J. Pisanchyn Jr., founder of the Scranton-based Pisanchyn Law Firm, said his staff uses artificial intelligence for a number of out-of-court tasks.

“We don’t use AI-generated documents to file in court, but we use AI-generated documents to assist us in our daily work,” Pisanchyn said. “We have strict protocols.”

Pisanchyn, who described Mehalchick’s order as “cutting edge,” said the online platform AI Chatting allows users to respond to emails by pasting in the original message and then typing in the general ideas they want to convey. The platform even allows users to adjust the tone of the email to sound professional or more friendly, he said.

“It’s pretty awesome,” he said. “It writes a perfect email.”

Pisanchyn said AI also helps his firm summarize medical records to double-check case overviews and to help in reviewing and summarizing voluminous records for demand letters.

“We have a new case-management system, which now basically has the AI feature in regard to summarizing notes and medical records,” he said. “For basic cases, it’s perfect. We always double-check, just to be sure. … Then we know if it missed anything. Sometimes we see it does, and sometimes we see it doesn’t.”

While artificial intelligence is getting some use in the civil arena, it appears to be less popular in the criminal justice system.

Luzerne County District Attorney Sam Sanguedolce said he has not come across any AI filings locally and that he does not permit his staff to use it.

“I know they’re not using it, and if they want to begin using it they’ll have to clear it with me,” he said. “We would disclose it as well.”

But he also said he has a lot of concerns about the use of AI, which has been known to generate fictitious caselaw citations.

One such example occurred in New York last year, when a federal judge presiding over a civil injury case fined two lawyers with the firm Levidow, Levidow & Oberman for submitting a legal brief containing nonexistent case citations conjured up by ChatGPT.

“Obviously, we have ethical standards that we have to live by, and anything we put on paper and sign and submit to the court, you’re testifying as an officer of the court that it’s true and correct,” Sanguedolce said. “So if a computer makes a mistake, you’re stuck with it, and you’ve submitted something to the court that’s false.”

Similarly, lawyers at the Pennsylvania Office of Attorney General do not use artificial intelligence due in preparing court documents.

“We find AI technology to be unreliable for document drafting, and staff does not use it for that purpose,” spokesman Brett Hambright said.

Federal authorities are also grappling with the emerging issue of AI use in court documents.

Dawn L. Clark, a spokeswoman for the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Middle District of Pennsylvania, said the Justice Department “is working towards implementing comprehensive AI governance processes, consistent with Executive Order 14110.

That order, issued by the White House on Oct. 30, 2023, directed federal departments and agencies to develop guidelines to assure that AI use will be “safe and secure.”

“My Administration cannot — and will not — tolerate the use of AI to disadvantage those who are already too often denied equal opportunity and justice,” President Joe Biden’s order read. “From hiring to housing to healthcare, we have seen what happens when AI use deepens discrimination and bias, rather than improving quality of life.”

The order gave the attorney general one year to submit a report to the president addressing AI use in the criminal justice system. It also directed the attorney general to have the department’s Civil Rights Division come up with ways to prevent “algorithmic discrimination” due to the use of automated systems.

Rising concerns

The issue of AI being used in court documents has generated enough concern in legal circles that the Pennsylvania Bar Association’s Committee on Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility issued a joint opinion along with the Philadelphia Bar Association earlier this year, noting that the technology “has fundamentally transformed the practice of law by revolutionizing various aspects of legal work.”

The groups noted that in addition to AI being able to help predict legal outcomes and manage cases, generative AI can help to automate document drafting, prepare summaries and analyze large volumes of information to allow attorneys to focus on other areas such as legal strategy and client needs.

But attorneys who choose to use the technology need to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the final product and be transparent about how they are using AI, according to the opinion.

“Artificial intelligence and generative AI tools, like any tool in a lawyer’s arsenal, must be used with knowledge of their potential and an awareness of the risks and benefits the technology offers,” the opinion concluded. “They are to be used cautiously and in conjunction with a lawyer’s careful review of the ‘work product’ that those types of tools create. These tools do not replace personal reviews of cases, statutes, and other legislative materials. Additionally, although AI may offer increased productivity, it must be accomplished by utilizing tools to protect and safeguard confidential client information.”

The concerns are not without merit. In a study whose results were released earlier this year, Stanford University’s Regulation, Evaluation, and Governance Lab found that rates of AI’s tendency to “hallucinate” — to make up false or misleading information — ranged from 69% to 88% in response to specific legal queries.

The lab concluded that legal hallucinations are “pervasive and disturbing” in large language models such as ChatGPT, with the authors writing that they had significant concerns about the reliability of AI’s use in legal contexts.

Concerns about AI’s reliability even prompted U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts to address the issue in his 2023 year-end report on the judiciary. He noted that AI hallucinations have resulted in attorneys submitting briefs with citations to non-existent cases, and that there are also concerns about due process when computers begin making the decisions.

“Any use of AI requires caution and humility,” Roberts wrote. “In criminal cases, the use of AI in assessing flight risk, recidivism, and other largely discretionary decisions that involve predictions has generated concerns about due process, reliability, and potential bias. At least at present, studies show a persistent public perception of a ‘human-AI fairness gap,’ reflecting the view that human adjudications, for all of their flaws, are fairer than whatever the machine spits out.”

Aside from concerns about accuracy and fairness, some lawyers have also raised concerns about how effective AI can be in the courtroom.

Pisanchyn noted that there are many human factors an AI chatbot cannot take into consideration.

“In certain professions I believe AI is going to be immensely useful,” Pisanchyn said. “However, there’s nothing that can equal being a human being. There are human thoughts, human feelings that, when you’re making arguments, you have to take into consideration — who the judge is, who the defense lawyer is, who your client is.”

He said he thinks AI could be useful to attorneys for tasks such as writing documents like wills and contracts.

“But something where a human has to interact with another human, I think it’s going to be a lot more difficult for AI to catch up to that because of that human component that you can’t really read about,” Pisanchyn said.

…

Article written by James Halpin

Read the original article here